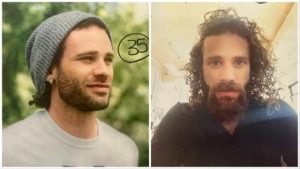

Race Day Live Ambrose Begay, a 28-year-old from the Alamo Navajo reservation in New Mexico, passed away from a fentanyl overdose near his home two years ago.

His death reflects a growing crisis among young Native Americans. Unlike the rest of the country, where overdose deaths have decreased, places like Alamo face rising numbers, highlighting a deeper, more localized epidemic.

Begay’s grandfather, Manuel Guerro, sees the toll this crisis has taken on his community. As a school liaison, Guerro witnesses the struggles young people face daily. On this reservation, where resources are scarce, the epidemic feels unstoppable.

Even though he has lost family to the drug, Guerro chose not to memorialize the spot where Ambrose died, wanting to avoid constant reminders of the tragedy.

National data shows a decline in drug overdose deaths, with a 21.7% drop in fatalities in the last year. However, the Alamo and other Native American communities have not experienced the same trend.

Overdose death rates in Alamo have skyrocketed, reaching 199 per 100,000 residents in 2024, far above the national average.

Alamo’s isolated location—85 miles from Albuquerque, accessible only by dirt roads—makes it hard to bring in necessary support. Residents have called for local police, detox centers, and rehabilitation facilities, but progress has been slow.

Many in the community believe that addressing fundamental needs like running water and food security is essential for long-term change.

The drug epidemic also ties into larger issues of generational trauma and neglect. Many young people, like Begay, turn to substances after experiencing loss, poverty, or systemic inequality.

Families are struggling to cope, often resorting to desperate measures like padlocking their homes to prevent theft by addicted loved ones.

Efforts to address the crisis face significant challenges. Police response times are slow due to the absence of local officers.

Health advocates, like Harold Peralta, work tirelessly to get people into rehabilitation, but many who seek help struggle to stay clean. Facilities are often far away, and the stigma around addiction makes recovery even harder.

Read More:

- Illinois Lawmaker Pushes to Cap Property Tax Levies at 2025 Levels

- Budget Friendly Retirement: 9 Places in Indiana Ideal For Your Golden Years in 2025

Some tribal members, like Myreon Apachito, have managed to break free from addiction. Apachito, now a team leader at Walmart, credits his recovery to a rehabilitation program outside the reservation. His story highlights the importance of accessible support systems, which are currently lacking in the Alamo.

Leaders like Michelle Abeyta and former law enforcement officer Cecil Abeyta are working to bring change. From pushing for local police to advocating for drug treatment centers, they believe that solutions are possible.

However, they emphasize that it will take more resources and cooperation between tribal, state, and federal governments to make a real impact.

As the fentanyl crisis continues to devastate Alamo, residents hope for a future where their community can heal and thrive. For now, they fight to save lives, one step at a time.

Disclaimer- Our team has thoroughly fact-checked this article to ensure its accuracy and maintain its credibility. We are committed to providing honest and reliable content for our readers.

+ There are no comments

Add yours